MR B. F. EASTLEY, MATHEMATICS TEACHER

This essay provides a brief overview of a fascinating period of musical development during the latter half of the fourteenth century, during which some of the most sophisticated music ever written was composed and performed. The ‘Ars subtilior’ or ‘subtler art’ (a 20th century musicologist’s title) is a repertory of several hundred songs by French, Italian, Flemish, and Spanish musicians. This music is quite distinct from other contemporary compositions due to its dazzling complexity in all aspects – particularly rhythmic – but also harmonic, textual, and sometimes visual.

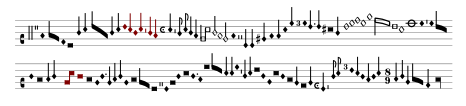

The composition shown at the beginning of the essay is from the Codex Chantilly, an Italian manuscript compiled in the early 15th century, which is considered to be one of the predominant sources of Ars subtilior repertory (alongside the Modena and Reina codices). Cursory examination will allow a contemporary musician to recognise the familiar 5-line stave and some semi-familiar note symbols. Beyond this point, however, a cornucopia of difficulties arise: why are some of the note shapes elongated or written in red ink? Why is text missing almost entirely from some voices? Why is the music written in the shape of a heart? What performing forces should be used to perform this music – solo voices, a choir, instruments?

Careful work by generations of musicologists have answered some of these questions, particularly regarding the unfamiliar (mensural) notation. The elongated notes are ligatures, a notational concept borrowed from earlier ‘modal’ notation (Yudkin, 1990) which typically collect multiple notes into a single melismatic gesture over which one syllable would be sung. The red notes (‘coloration’) are in most cases shortened by one third, allowing for rhythms that are cumbersome in modern notation to appear quite straightforward in their original format. This is illustrated by the following extract from Baude Cordier’s ‘Belle, bonne, sage’ in which the first two staves are written in mensural notation, and are followed by their modern equivalent.

Additional features of notation from this period allow for binary and ternary note subdivisions between breves and semibreves (‘tempus’) and between semibreves and minims (‘prolatio’), modification of those subdivisions according to sophisticated rules of precedence established by music theorists of the period (Pseudo-de Muris, 15th C), and exact proportional relationships between different sections of a composition without the use of metronome marking (not to be patented until 1815 by J. Maelzel). These are illustrated in the table below.

Unfortunately, other questions about this repertory are still unanswered, and we do not expect to find definitive solutions. For example, the question of which performing forces to use for this repertory (or indeed all medieval music) has not been satisfactorily answered despite decades of research. Early 20th century musicologists grappled with the question of performing un-texted parts in medieval music, and there is still no conclusive answer. Recordings from the beginning of the early music revival in the 1970s typically used multiple voices and an exceptionally wide variety of reconstructed instruments (Greig 2003). Musicians and musicologists from that period pointed to the questionably vocal nature of the untexted parts, with notes held for very long periods, unintuitive leaps, and no obvious means to apply text in a sensible manner to the musical line. Such an unsupported assumption was hazardous leading to anachronistic performance practice, and musical manuscripts, theoretical treatises, and even artwork have since been used to refute it (McGee 1993). Contemporary performers typically use one voice per part and unworded vocalisation for unvoiced parts, although there is still vigorous debate regarding these issues.

Regrettably, however, medieval musical performance practice remains a musicological hydra: whenever one solution, however tentative, is found, another two questions arise. Even if one is able to read the musical notation accurately, has learnt the intricacies of historically-accurate pronunciation of the musical text, and is technically capable of performing the music, there are still issues of performing speed, vocal timbre, ornamentation, and performing pitch to consider. These questions are unanswerable with certainty and performers are inevitably required to make a series of educated guesses. As Christopher Page, the eminent medieval music specialist notes: “To study the performance of medieval music is to approach the edge of a cliff. We can go so far and then the evidence abruptly comes to an end, leaving a sheer drop into a sea of troubles where performers must navigate as best they can.” (Page, 1992, p. 446)

Difficulties of interpretation and performance are especially acute when considering the Ars subtilior repertory, as it was a relatively short-lived style which appears at first glance to be intentionally difficult to interpret and perform. A question which therefore naturally arises is why would such demanding music ever be written? To begin to answer this question, the historical and social context in which it was composed must be considered. For the majority of the 14th century, the papacy was not based in Rome, but rather at Avignon in the south of France, because of a variety of complex political disputes between the papacy and the French crown. In 1376 Pope Gregory XI returned to Rome and, after his death in 1378, the religious landscape of Western Europe was torn asunder by the Great Schism. During this period, there were two (or occasionally three) men claiming to be the true pope. This dispute would eventually be settled at the Council of Constance in 1417, but prior to this resolution, two ‘antipopes’ successively ruled from Avignon (Clement VII and Benedict XIII). They naturally made every effort to demonstrate their legitimacy and power, and one aspect of this was patronage of the arts.

Patronage of musicians was, by this time, a well-established means for the nobility to culturally enrich their courts and demonstrate their wealth and good taste to their peers. Musicians were employed to compose and perform new music for both religious and secular occasions, as evidenced not only by financial records but also by specific references to weddings and other significant events within many compositions. For example, several ballades by Solage, the primary composer represented in the Codex Chantilly, refer to John, Duke of Berry and his second marriage to Jeanne de Boulogne in 1389. In fact, dedicatory ballades can be found throughout the Ars subtilior repertory directed to French princes, cultural centres throughout northern Italy, and naturally the antipopes in Avignon. Evidently, the nobility across a substantial portion of southern Europe were quite content to support the production and performance of exceedingly avant-garde music.

It may be tempting to attribute the dazzling complexity of the Ars subtilior to a mere passing fashion among the nobility of the time. However, this would be a considerable disservice to the composer-performers who took advantage of the advanced capabilities of mensural notation, and coupled this with both a deep appreciation of textual trickery and a willingness to experiment with different concepts of musical purpose. Certain pieces appear to have the performer as the intended audience, whereas others delight in finding novel means of praising their patrons, whether shown in the visual layout of the manuscript, or in textual acrostics (Stone, 2018). There is a general sense of pushing all boundaries simultaneously throughout this repertory, leading to the celebrated 20th century musicologist Willi Apel charging that the “musical notation far exceeds its natural limitations as a servant to music, but rather becomes its master, a goal within itself and an arena for intellectual sophistries.”. (Apel 1961, p. 403)

Although Ars subtilior was a short-lived style, it had a lasting impact, arguably being the first time in European history that the composer is considered an independent creative figure: a concept now considered an integral part of the modern definition of that role. Additionally, although its excesses would not be seen again until the 20th century (e.g. the music of Conlon Nancarrow), some aspects did survive in succeeding generations. For example, the ‘Missa prolationum’ by Johannes Ockeghem, dating from the late 15th century, is a four-part setting of the Ordinary of the Mass (Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus and Benedictus, and Agnus Dei) for which only two parts are written in the original score. The other two parts are derived in real-time by the performers singing the written lines with modified ‘tempus’ and ‘prolatio’, resulting in their parts effectively progressing at varying speeds (and with additional rhythmic alteration) to the written parts. This mass setting is the crown jewel of the ‘mensuration canon’, a compositional practice which persisted in a simplified structure in the form of augmentation and diminution canons, such as those found in Bach’s appendix to the Goldberg Variations (BWV 1087). To perform Ockeghem’s work from facsimile editions rather than scores in modern notation is sufficient to test even the most able and historically-informed musician, requiring a degree of fluency with early music notation that can only be acquired after years of study. It is, like the Ars subtilior repertory from which it is descended, an intellectual challenge which appeals to a particular subset of performers.

For many modern audiences, the extravagances of the Ars subtilior repertory, with all its hidden subtleties and blatant intellectualism, are a step too far. Certainly, for the uninitiated, the vast majority of the textual and musical detail will pass unnoticed in a haze of technical prowess despite the best efforts of performers. In many ways it really is music for musicians, not for the lay-public. However, the Ars subtilior repertory is the product of a fascinating and complex period of European history, in which composers reached, like Icarus, rather too close to the sun. Some aspects of the Ars subtilior style survived and flourished in later compositional practice, but its greater eccentricities rapidly dwindled away. For a few short decades, however, a small elite collection of European musicians had the opportunity to write and perform music that would not be significantly rivalled in complexity for another 500 years. Their candle burnt only briefly, but its flame shone brightly indeed.

Bibliography

Apel, W., (1961) The Notation of Polyphonic Music 900–1600 5th ed. Medieval Academy of America.

Greig, D., (2003). Ars Subtilior Repertory as Performance Palimpsest. Early Music. 31(2), 197–209.

McGee, T. J., (1993). Singing Without Text. Performance Practice Review. 6(1), Article 8.

Page, C., (1992). Going beyond the limits: experiments with vocalization in the French chanson, 1340-1440. Early Music. 20(3), 446-459.

Pseudo-de Muris, J., (15th C). Ars Discantus, MS. Bodl. 77. Bodleian Library, Cambridge.

Stone, A., (2018). Ars subtilior. In: M. Everist, T. F. Kelly, ed. The Cambridge History of Medieval Music. Cambridge University Press. vol. II, ch. 37, pp. 1125–1146.

Yudkin, J., (1990) De Musica Mensurata: The Anonymous of St.Emmeram - Complete Critical Edition, Translation and Commentary. Indiana University Press.

Discography

Baude Cordier - Belle, bonne, sage

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LNKiFrMMSlQ

Solage - Fumeux fume par fumée

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0_rH2a-rg6Y

Baude Cordier - Circle Canon, "Tout par compas"

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iaeOWdXM4Pg

Johannes Suzoy - Pictagoras Jabol et Orpheüs

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nVkWSrgI2co

Rodericus - Angelorum psalat tripudium

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9p2rqajJHro

Antonio Zacara da Teramo “Rosetta che non canbi mai colore”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gle0oJbaX4c

Comments

Post a Comment